Blind Spots

Changing lanes When experienced drivers change lanes, they know well to look out for vehicles or other objects that are in their blind spot. Objects that are in a blind spot, cannot be seen in either a vehicle’s rear- or side-view mirrors. So the driver has to know to glance over her shoulder so that […]

First of the First Quarters

Our first quarterly review Market Context The Lunar BCI Worldwide Flexible Fund (LBWFA) was launched on 1 June 2016. In our first quarter to 31 August 2016, several significant events have been playing out locally and globally, which impact the investment markets: The ongoing, so-called SARS war between the South African Finance Minister and his […]

Some Things Are Best Done Slowly

Kilimanjaro Last month, my wife and I, together with eight great friends had the very challenging opportunity to hike up to the highest point in Africa, Uhuru Peak on Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania. Uhuru peak is at 5895 metres above sea level and is also the highest free standing mountain in the world. We had […]

Blexim – Starting a fund now!

Curse or Blessing in disguise? Lunar Capital, the company I co-founded last year and Boutique Collective Investment Schemes have partnered and launched an investment fund (Lunar BCI Worldwide Flexible Fund) on 1 June 2016. If someone had told us that Brexit was going to happen later in the month, I’m pretty sure we would have […]

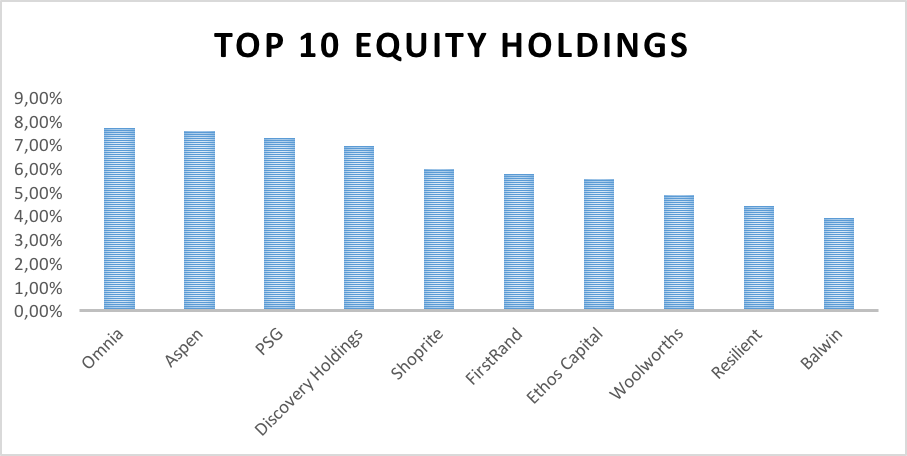

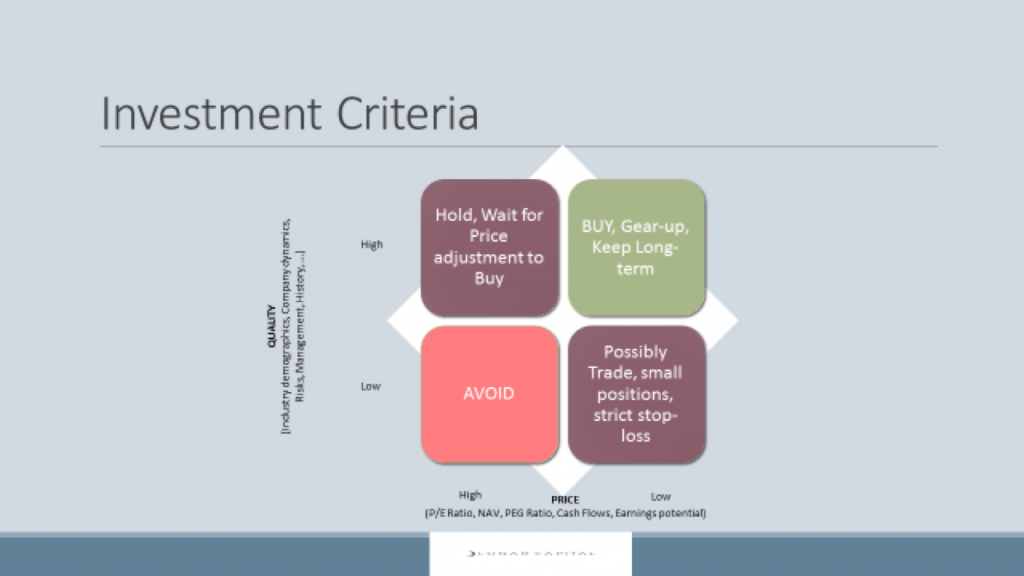

Investment Selection Methodology

Over many years of investing, one develops an investment philosophy and approach that you start feeling comfortable with. You know that it is not risk free, but you are confident that it gives you a framework for making your investment decisions. It’s also not cast in stone, so you are continuously making adjustments to it […]

Thoughts on investment strategy in the current market

In this blog, I want share with you some of my thinking on how I would position an investment portfolio in the current market. Central banks The current market in South Africa and globally is influenced by a number of factors. What stands out for me however is the role of central bankers in trying […]

Investing in Turbulent Times

We are currently bombarded with negative news, globally as well as in South Africa. There’s a lot of noise about the poor global economy been weak, poor demand from China with significant ramifications for resource based economies, economic and political woes in South Africa, etc. It is natural then that investors or potential investors find […]

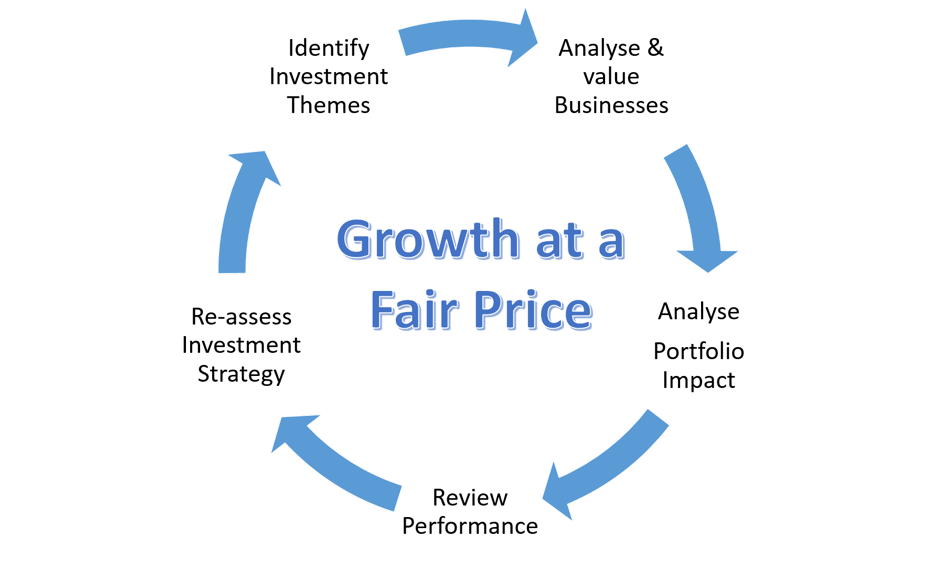

Growth at a Fair Price

In this blog, I want to share the investment philosophy and approach that I use for my own investments. I have termed it Growth at a Fair Price. In my previous blog, Developing your Investment Philosophy, I discussed how you should develop your investment philosophy and approach that is suitable for you; given your circumstances, […]

Developing Your Investment Philosophy

Investing is not easy. Even after many years of studying and experience in investing, many investment managers can still find themselves flummoxed by the markets. Yet, everyone should have a strategy for investing for their futures, so that they can increase their personal value (#MyPersonalValue) and get the benefit of time in (not timing) the […]

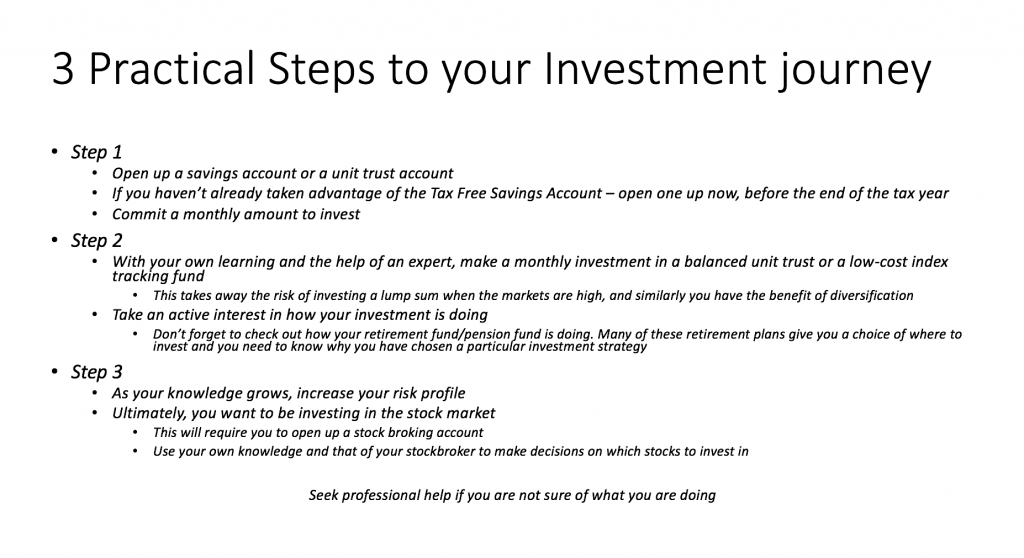

Why you need to start investing now.

This is the transcript of a talk that I am giving to the staff of various organisations and groups of individuals and the topic is “Why you need to start investing now”. I am incredibly grateful that I have had an interest in investing from a very early part of my adulthood, both in seeking […]